It Came Out of Liverpool, Laughing: The Wit of the Beatles

In the 1950s and '60s, Liverpool was a hard, rough port town that offered many dead-ends and few opportunities for upward mobility. Liverpool did have idiosyncratic humor shared by the city's residents and used as a balm to ease the often crushing burden of their day-to-day living reality.

In Liverpool, verbal jousting is an art form. Scouser wit – often delivered in a deadpan style, is sharp and often biting. Even their name for themselves – Liverpudlians – is the Scouser's inverted joke in which the pool becomes a puddle.

Why does the River Mersey run through Liverpool? Because it doesn't want to get mugged.

Into this fermented puddle of wit - where a sharp sense of humor was required, and one was judged by its quality - the Beatles were born, both as individuals and as a band. Scouser wit was the spine of their career, affecting every aspect of their existence and responsible for their initial success until their songwriting caught up.

John Lennon's humor was often underpinned by the dark nature that was part of his personality. Separated from his father, Lennon was left by his mother to live with his aunt. Then his mother died in a tragic accident, and soon after that, his beloved uncle also died unexpectedly. Lennon used humor to cover the pain of abandonment by those he loved most. Early in school, that humor took increasingly sharp turns towards the surreal and often cruel in poems, stories, and illustrated magazines he created to communicate with the outside world.

Tragedy struck Paul McCartney early when he lost his mother in his fresh teens. He was always a people pleaser on the surface, so while his sense of humor could also take sharp and biting turns, this was often obscured under layers of protection.

George Harrison came from a family that was affectionate, loud, and immersed in-jokes and cut-ups. Inaccurately referred to as the Quiet Beatle, George was a talker whose wit took a dry, sarcastic tone.

The Reeperbahn, Hamburg's seedy red-light district, was the anvil on which the group hammered themselves into the best live act of Northern England. They had several lengthy stays here playing at loud and often dangerous clubs, sometimes backing strippers. The lubricant that greased their way through this maze of dangers and endurance was humor.

John, Paul, and George quickly found their shared sense of humor helped grow the intense bond they shared. They riffed off of each other like veteran comedians, often finishing their jokes and jabs. But entertaining the jaded, uninterested thugs and blue-collar workers who made up the clientele at the Reeperbaum's Kaiserkeller, Top Ten Club, and Star Club took more than music - it took jokes.

Lennon trotted out his well-worn cripple routine or ridiculed the crowd with Nazi jokes and Hitler imitations. Once amphetamines entered their world, the comedy took on an increasingly manic persona. So wearing a toilet seat around his head while playing in his underwear was another tool in Lennon's entertainment chest.

Their personalities, imbued with that unique bond and sense of comic surreality, helped Brian Epstein see their potential. But pushing them on every record label in England came to nothing for the aspiring, young manager with a passionate belief in his charges. His last hope was George Martin, who headed the poor relative record label Parlophone.

Martin's first recording success was in comedy, recording Beyond the Fringe, a comedic stage review featuring Dudley Moore, Peter Cooke, and Jonathan Miller. Those records are considered a critical linchpin in Britain's ascendance of satiric humor.

He followed that with recordings by Peter Sellars, a comedic phenomenon who seemed capable of doing anything. Along with his solo recordings of Sellars, Martin also recorded him as part of a group including Spike Milligan and Harry Seacombe, known as the Goons. Through that process, he became close friends with Sellars and Mulligan.

The Goons were something completely original. Their unique blend of surrealism, crazy plots, and startling sound effects made an enormous impression on the young minds of the time. Most notably on John Lennon and Paul McCartney, who regularly name-checked the Goons. Sellars would repay the favor with his hilarious reading of their "A Hard Day's Night."

The Beatles knew who George Martin was and respected him more than most adults for what he'd done. While Martin didn't see enough in their demo tape to sign them, he agreed to have them come to London and record in his studio at Abbey Road to give them a better chance.

Martin handed the group off to Parlaphone producer Ron Richards and engineer Norman Smith to record. They were unimpressed. They liked the boys, but the material and performances were lacking, and they took some pleasure in telling the young band so. When Martin came in to hear the recordings, he shared their opinion but was more reticent in saying so.

In his polite, English manner, Martin asked the band if there was anything they didn't like, meaning in regards to their recordings. George Harrison replied: "Well, I don't like your tie." There was silence. In 1950s England, you didn't talk to your betters that way. Martin noticed the smile dancing on the edges of Harrison's mouth. Having improved Parlophone's standing by recording comedy, he knew a joke when he heard one, and he smiled ear to ear at this one.

The ice now broken. John, Paul, and George went into full Beatle mode, riffing off each other with the improvisational skill of professionals. Richards and Smith remember laughing so hard they were crying in their sleeves. Martin knew then he would sign them based not on their music but their personalities and sense of humor.

Still, there was one problem – the unimaginative drummer who could do little more than pound out a 4/4 beat and had the personality to match his drumming skills. Pete Best was not like the rest – while they joked with Martin, he stood quietly, saying nothing. Martin's desire to use another drummer on the session cemented the already growing sense of the other three that Best had to go. They left the dirty work to poor Brian Epstein, but it was clear that Pete wasn't a Beatle, as Lennon said. Ringo Starr, however, was Fab.

The poorest of the four Beatles, Ringo was his mother's only child. His father had abandoned them, and his good-hearted stepfather solidly filled the father role for him. A sickly child, he spent months in the hospital and in his home recuperating. Indeed his humor was formed in part by these experiences. But it was his cheerful, regular guy personality that affected it more. With his non-sequiturs and malapropisms, Ringo often didn't even know he was being funny. He filled the fourth side of this quartet perfectly, often playing the willing foil to their lunacy.

The America that the Beatles took by storm in 1964 was a gray and unhappy place. The public murder of the country's young president in Dallas had thrown the nation into a depression of confusion. Lacking Britain's acceptance of the unusual, or its appreciation of the surreal, the country was stolid and square.

With its simple yet alluring melodies and arrangements filled with musical examples of humorous quirks, the Beatles' songs were joyous and exuberant: the perfect elixir for a country in mass shock. But it was their humor that lifted them above everyone else.

Upon arriving, their press conference at the New York airport was another sign of a fresh wind blowing into town. The irreverent and cheeky wordplay immediately won over the jaded press corps, making them willing allies in this new invasion. The jousting between the two camps was like an electrical current repeatedly spiking, nearing explosion.

Q: How did you find America?

John: Turn left at Greenland.

Q: What did you think when your airliner's engine began smoking as you landed today?

Ringo: Beatles, women, and children first!

Q: What do you think of the criticism that you're not very good at?

George: We're not.

Self-deprecating, good-natured, and brimming with youthful energy, they also had some understanding of what they had gotten into and the atmosphere that surrounded them. This, too, was served up with a healthy dose of Lennon's black wit.

Q: Are you scared when crowds scream at you?

John: More so in Dallas than other places.

Humor continued to be their trademark in press conferences and onstage. It became the armor that protected them against the madness that surrounded them. And it also served to alleviate the utter boredom of stupid questions and the fever of being besieged in a hotel, then a car, then a backstage, then a car, then a stay, then a hotel, and on and on. Beatlemania became a trap, and humor was the only escape.

The screenplay for their first film, A Hard Day's Night, by Liverpudlian Alun Owen, was not so much written as received. Owens spent several days with the band, watching their lives and absorbing their personalities. The screenplay was an honest reflection of the madness they were experiencing while at the same time a true reflection of who they were as people.

So much of what we love in A Hard Days Night is the Beatles being the Beatles. A good portion of Hard Day's Night's written dialog was taken from what the four Beatles actually said in the company of Owen. And since they were not trained actors, director Richard Lester smartly allowed them to improvise while keeping the camera rolling.

That Lester was the director of their two notable films was no accident. The Beatles had picked him from a list of directors because of his earlier The Running Jumping and Standing Still Film. This classic film, shot over two Sundays in 1960 by the American-born director, is a short 11-minute bit of filmed lunacy featuring the Goons. It was a big favorite of the Beatles, and Lennon, in particular, was obsessed with the fi

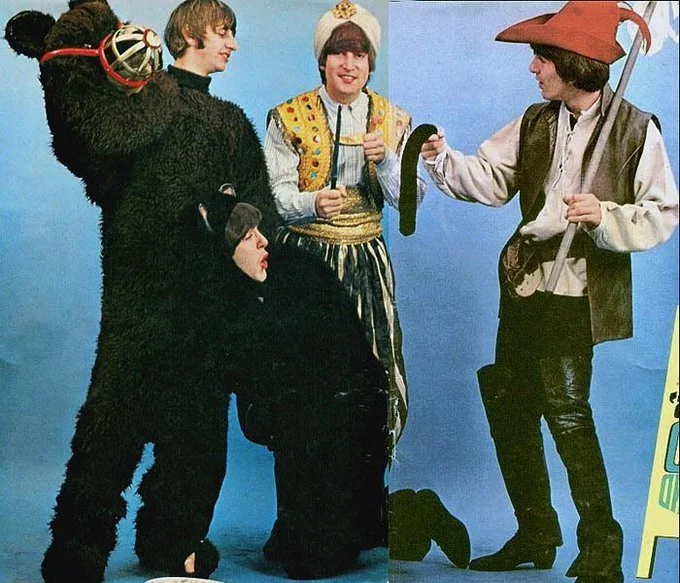

The band's follow-up film Help! suffered from the explosive success of the first film, but intervening years allowed it to be taken on its own merits. The film is a complete investment in surreal dialogue, bizarre characters, and crazy plot twists – quite like the Goons.

John: [finding a season football ticket in his soup] What's this?

Ringo: A season ticket. What do you think it is?

John: Oh. I like a lot of seasoning in my soup.

Or:

Ringo: I like operations. They give you a sense of outlook, don't they?

The Beatles' self-made film, Magical Mystery Tour, was roundly sacked when shown on British TV on Boxing Day in 1967. Incredibly, in a world now inundated with psychedelic colors, the film was the first show in black and white. All the more detrimental because the original film itself was awash in color. Time has been kind, and it is now sometimes reappraised as a surreal near classic. Still, even on its release, Magical Mystery Tour was enormously influential on one like-minded group of young men.

Monty Python would not form until a year after the Beatles broke up, but it's easy to see their template in both Help! and Magical Mystery Tour. Python's Terry Gilliam has noted that Python was often referred to as the comedic Beatles. The connection between the two irreverently funny forces was made formal when George Harrison started a long friendship with the Python members and became a backer of many of their films.

As they approached the recording of the seminal Rubber Soul, the band feared that they needed a new direction; otherwise, their sound would be stale. They toyed with the idea of writing comedy songs. Out of this idea came the comedic character study "Drive My Car." Here the object of our protagonist's affection is a determined aspiring star. His reward for fealty to the girl is a job as her chauffeur – even though she doesn't yet own a car.

While it is rightly the music that the Beatles' legacy is built on, humor invades and permeates even here. It showed up in the music in often unusual ways – impish arrangements or vocals, subversive words or lyrics. Sometimes it's in little jokes, as in the song "Girl" where, like naughty schoolboys, George and Paul sing in the background "tit-tit-tit." Or, in the same song, when Lennon inhales like he's smoking a joint, their own inside joke.

Norwegian Wood also had some comedic intent. McCartney's idea to have the song end with the protagonist burning down his paramour's house had the Fabs in stitches. Of course, few others got the joke.

The Beatles were nothing if not inveterate capitalists and not ashamed of it. Harrison had some money to call his own for the first time in his life. England's tax laws meant that bigger earners were paying 95% of their income to the government. An outraged Harrison penned the bitterly sarcastic "Taxman" in reply to a government that gave "one to you nineteen for me" and then demanded that Harrison not "ask me what I want it for."

The White Album's "Bungalow Bill" is an aural comic book, while "Why Don't We Do It In the Road" is at the same time McCartney's dirtiest and funniest song.

The Goons

The Goons spirit infiltrated many of their songs: "Yellow Submarine," "Hey Bulldog," and "Wild Honey Pie" all use the Goon formula of sampling in the surreal while using bizarre sound effects to enhance the underlying humor. "You Know My Name (Look Up the Number)" and "What's The New Mary Jane" were both beholden to the Goon ethos. The former is a simple lyric repeated as a mantra, with only the backing track changing styles. The latter is a string of nonsensical Lennon-isms wrapped in a loopy musical arrangement.

Taking a word, playing with it, and using it creatively is a very Liverpudlian humor trait. The Beatles were gifted artists in this arena. Sometimes it was accidental, as in the case of Ringo's malapropisms, which brought new meaning to the ridiculous and often found their way into Beatles songs and titles. The titles "A Hard Day's Night," "Tomorrow Never Knows," and "Eight Days a Week" all started life as unintended wisdom flowing from the Fab drummer's mouth.

McCartney got into the game by naming Rubber Soul – a joke on the white man's version of soul music. Lennon's "I Am the Walrus" was the most overt and intentional usage of this brand of Liverpool humor. It displays a love of words for their own sake, giving meaning where none is intended.

Their Christmas records and fan club recordings were the most outstanding example of the Beatles' Goonsian wordplay, with sound effects and general surreal humor. These absurdly funny recordings contained virtually every element of Beatles humor, including memorable musical melodies with half-cracked lyrics.

Brian Epstein's assistant, Alistair Taylor, attributed one genuinely surreal bit of inside musical humor to McCartney. He claimed that the outro of "All You Need Is Love" was McCartney's idea of a joke: towards the end of the song, the band begins playing in a different time signature and style, as if they just realized they'd been playing the music wrong the previous 2 ½ minutes, and this last bit is the right way.

The Beatles were incredible pranksters, both in life and in art. They got perverse joy from doing what was not expected so that they could watch the resulting reactions. Paul McCartney wryly noted, "if you don't live this life with a sense of humor, it could soon get you down." It's no wonder that when Neil Innes released his Beatle parody film, the Ruttles, the former Fab Four laughed first and loudest at the film.

The Beatles profoundly affected the American sense of humor and its appreciation of the surreal and ridiculous. Nothing would be the same again. If you are genuinely listening to them today, you're still laughing, and life is much more bearable.

After all, nothing is real and nothing to get hung about.